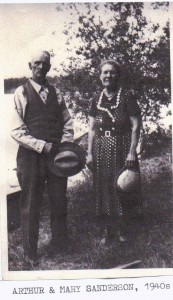

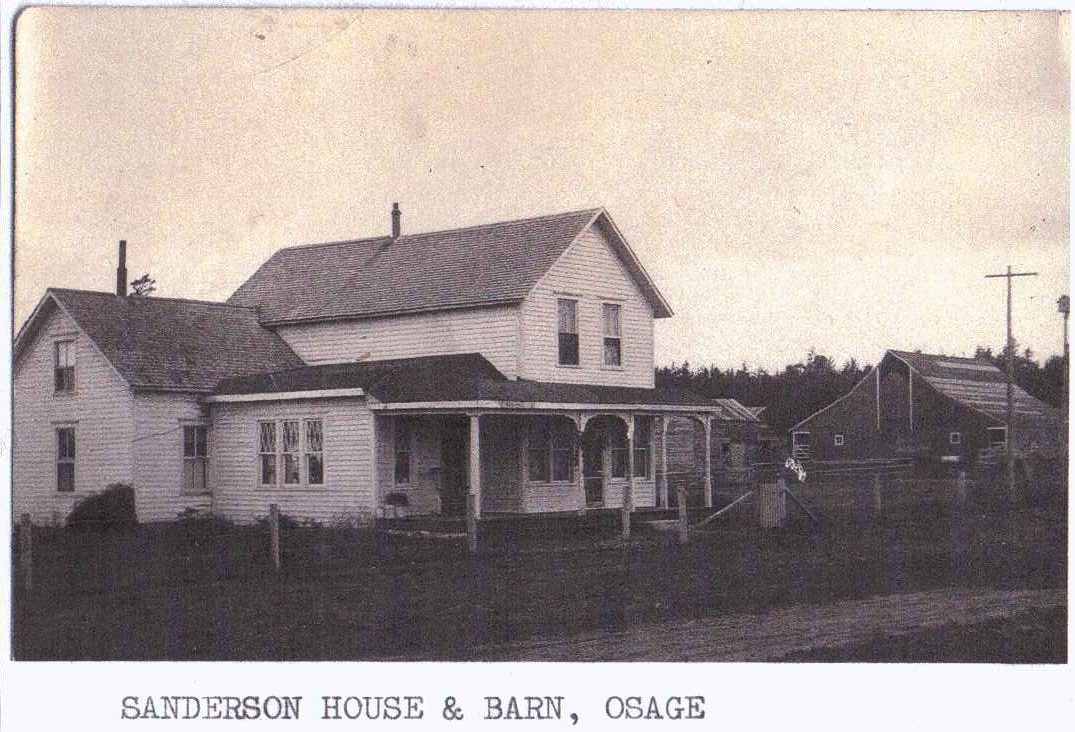

A.W. & Mary Sanderson home, burned down in 1929.

It all began for me in the small village of Osage in northern Minnesota in the month of February, in the home of Sadie Poole, a practical nurse (that means no medical training), in a very cold upstairs bedroom heated only by a pot belly stove on the floor below and under the orange glow of kerosene lamps. Obviously, I was too small, and as yet unformed, to have any memory of it. But, that was Osage in 1927, a village without electricity. We’ll talk much more about the town and the people that lived there at that time.

I’d like to have you look at all this through my eyes as I saw it at the time, not as I see it now through 20/20 hindsight. As you might guess, there is a huge difference as to how we see things with a lifetime of experience behind us.

As you know, for every beginning there is also an end. That’s what’s important here. Not just what is lost in the end, but how it compares with what was gained in the end, or if not gained, then simply changed. So, the closer you can come to seeing the way it was back then, the better able you will be to judge the change and its value, if any.

To get in the right frame of mind, let’s first take a look at a quote from Albert Einstein where he explains why we tend to fabricate mental constructs that we desperately want to believe in: “Man tries to make for himself a simplified and intelligible picture of the world. He makes this cosmos and its construction the pivot of his emotional life in order to find in this way the peace and serenity which he cannot find in the narrow whirlpool of personal existence.” But, as I said earlier, that will come later in this narrative when we look back with 20/20 hindsight.

Skipping slightly ahead one more time I remember as a school-age kid being totally enchanted when I read that some twenty-four centuries ago, the Greek philosopher Plato, in his allegory of the cave explained that man is like a being chained inside a cave watching shadows on a wall and from these inferring what the world is about but does not perceive that from his limited view he does not realize that what he believes to be right is actually wrong. It should be noted here that the word philosophy, by the way, means search for wisdom. That is probably a good starting point to examine any and all beliefs. Sometimes not and sometimes it is, but only if the teacher hasn’t already drawn a conclusion. I remember much later in life in my classes on philosophy the teacher was a communist from Greece. So, there were a lot of tales like this one about the wolf cub who was raised with a flock of lambs and occasionally had these strange urges to nip at his little friends. Then, one day he grew up and understood that he was a wolf, and lo and behold, they were sheep. I think you can see where that one was going.

Personally, I am of the opinion that many things in life are not only uncertain, but also unexplainable. It is quite obvious that the natural world is a complex, interconnected system. The mistake is that we think because we are in various ways able to manage parts of that system, usually through trial and error, that we also understand the whole of it, when in fact, we only understand the miniscule part that we have rearranged to our advantage.

Perhaps later in this narrative I can describe some of my own experiences living in different parts of the world under very different cultures and religious systems. While I have, so far, never had so-called end of life or after death experiences there have been as I mentioned some that deny rational explanation. I will let you examine them and draw your own conclusions when we reach that point.

So later on we’ll continue to sift through all of these things and others, but enough of the heavy stuff for right now. I’ve raised doubt which, in itself, is an important beginning for any examination of so-called truths. Doubt is important. Especially to me since my given name is Thomas. Remember from Sunday School, ‘Doubting Thomas’. So you’ve come to the right place for an examination of doubt. But, I leave examination of your belief system up to you.

Speaking of Sunday School, on rare occasions my mother actually manipulated me into going there dressed to the nines. At the time that meant waist length jacket, clean shirt, tie and knee-length knickers with wool socks that came up almost to where the buttoned cuffs stopped at my knees. It was a Baptist church. Mom actually preferred Presbyterian, but the only two churches in this village at the time were Baptist and Lutheran.

The Baptists literally scared the hell out of me.

I had the recurring nightmare of a huge white bull chasing me up and down the center aisle of the old wooden church that my grandfather had built for his fellow townsmen. I simply could not completely elude that insane bull. By the way, my grandfather wanted the church to be Latter Day Saints, but unfortunately for him the Baptists took it over. He apparently took that in stride, since he taught Sunday School for a number of years. (Long before my time.) Incidentally, the church was so well designed and solidly built with wooden pins and pegs that Minnesota’s Itasca State Park hauled it off to permanently reside in its replica of a pioneer village. I think its nondenominational now so I have no idea how my grandfather would have judged that.

Another Sunday School worry was that my three sisters—all older than I—were going straight to hell. After all, they smoked, danced, and probably took a few drinks, and maybe other things that I could only dimly imagine at that age. So I became resigned to the fact that I wouldn’t be seeing them in heaven where I smugly presumed that I would be. This really bothered me because they were obviously unrepentant and never once during the Baptist summer tent revivals came forward to be born again and baptized in the community swimming hole where the visiting evangelist would stand dripping wet up to his waist in his Sunday best suit while he submerged the repentant sinners. He pinched their noses so they wouldn’t choke and drown while he recited his little spiel. (The former sinners, by the way, only stayed on the true path for four to six weeks before they returned to the good life.) Looking back, I can’t say I blame them.

By the way, when I mentioned the potential sins of my sisters that were beyond my youthful comprehension, I was actually typical of boys my age at that time. A little chum of mine in the first or second grade was walking home after school to the family farm when he saw a couple of eighth graders, one on top the other, underneath a bridge. Observing more detail, at home he told his mother, “I saw Johnny peeing into Sylvia.”

So ‘born agains’ back then reverted rather quickly to their previous sins because life, at its very best back then in that remote village, was unendingly dreary and bone-weary hard. And at times, chillingly brutal. Th is was the beginning of the great depression.

is was the beginning of the great depression.

No doubt those sociology classes you took in high school sometimes stressed the innate goodness of man, like we all came from the same gene poll as Mother Teresa. Somehow, I find this idea to be almost diametrically opposed to the actual recorded history of mankind. Can you name any prolonged period of time that was actually peaceful? When there wasn’t an actual war in progress somewhere. If it appeared outwardly peaceful then it was only because some nation was taking the time to make the necessary preparations for war. For example, there have been more than 360 wars in the 20th Century, killing an estimated 160 million people. That averages out to be over 30 wars a year. Hardly a testament to man’s innate goodness.

Should you have doubts about this, you might consider reading Colin Turnbull’s book ‘Mountain People’, an anthropological study of the Ik tribe of Uganda in eastern Africa where individual survival is at its most extreme. So much so that in one case a mother rejoices because her daughter has been eaten by a leopard because it relieves her of the burden of taking care of the child.

At the other extreme is his study of a pygmie tribe in Zaire in his book ‘Forest People’, where social interaction is so ingrained that if a man is being harangued by his wife he can call for help and half the village will be there willing to offer him whatever assistance they can to relieve his stress.

Perhaps this suggests that whatever goodness exists in mankind is a learned acquirement rather than an inherited genetic predisposition.

Despite Edward Hicks’ painting of the Peaceable Kingdom where all the predators coexist peacefully with their prey, neither nature nor its beasts appear to be governed by benign instincts. Just as in our world, the powerful exploit the weak, at least they do when they can get away with it. Think Bernie Madoff. One of my first lessons in this real life classroom was the beating of Billie D.

Billie was not a particularly admirable character. He was short, feisty and without trade. Meaning he was at the bottom rungs of both the economic and social ladders in Osage where low meant poverty-scratching-low. The only really intelligent upward move Billie made in his life was marrying a very large-boned muscular woman who had just inherited the family farm located a few miles outside the village.

I remember one day overhearing one of the mechanics in my uncle’s garage kidding Billie that maybe he didn’t have a penis of sufficient length to satisfy this strapping farm woman. Billie confidently replied, “it’s big enough to make her fart.”

Directly across from my mother’s general store on State Highway 34 in the center of our town was a saloon. It was a small clapboard building so narrow that there was only room for a standup bar, no stools, not even a brass rail at the bottom of the bar though there were some spittoons since as many customers chewed tobacco as there were those that smoked it. It was just about as bare bones as a bar could get, though the beer was kept cold in ice boxes. This was before the REA brought the refinements of electricity to our community. And bar and store owners had to drag in forty-pound blocks of ice every morning and use an ice pick to chip them into a cupboard like, lead-lined, leak proof ice box, or cooler as they were often called.

One time, my brother Art, who was of drinking age and a good deal older than myself, saw me hanging around in the street outside the bar. He invited me in the bar to have a beer. This, of course, would have been kept from our mother who was totally against alcohol, with reason, but that’s another story. The barkeep handed me a Pabst, in a tall bottle, cold enough to cause sweat to drip down its sides. It looked delicious. Looking at the foam on top, I was imagining something like a sweet vanilla milk shake with froth on top. I took one drink, spit it out and walked indignantly out of the place. Laughter followed me into the street.

Art fancied himself as an outdoor man, which he was. I remember once hearing him talk with an older fellow that he had spent several days in the woods with cutting trees to be sent to a mill for lumber. Living by themselves in the woods they apparently weren’t overly careful about preparing their meals which came out of cans. What struck me was they seemed to be bragging about not washing their plates. They would apparently use one side one day and then turn them over and use the bottoms the next day. I thought that was a bit too much.

Anyway, often times after work, Billie would stand in the center of the bar and hoist a few. He could be irritating when sober and downright obnoxious when he had a few. On this particular evening, Percy was back from Minneapolis visiting his brother the bar owner. Percy was a good bit over six foot, muscled, with broad shoulders and togged out in big city finery. Billie in stained bib overalls didn’t quite come up beyond Percy’s chest. That, of course, didn’t make Billie less feisty. The upshot was they went out into the street. At that time, Highway 34 was just a widened one-lane dirt track between the larger towns of Park Rapids, ten miles to the east, and the county seat in Detroit Lakes, thirty miles to the west where the sheriff’s office was located when he was there.

The exchange of insults and the fight itself made enough noise to attract a sizeable audience in a village of less than two hundred people. My mother, my sisters, myself and the Baptist preacher who lived with his family in the parsonage which he had built down the block, were all there watching through the large plate glass window in the front of our store.

Percy, with fists the size of ham hocks was mercilessly beating the smaller Billie, despite Billie’s flailing fists on arms far too short to connect with Percy. It was a bully beating a puny runt to the ground and enjoying every bloody moment of it.

That’s when I first had serious doubts about the innate goodness of man. No one did anything to stop it. The preacher, a very large German with an accent thick enough to make his sermons only partially comprehensible, just watched. (Incidentally, why the Baptists sent a German-speaking preacher into a town where no German was spoken was another mystery.) My Uncle Les and the mechanics in his garage with enough monkey wrenches to stop an invasion also just watched. The other men in the doorway of the bar did the same. No one gave a hot damn whether Billie was killed outright or beaten into a state of serious mental impairment.

When Percy finished by kicking the downed figure with his size twelve wingtips, two men did have the decency to haul the unconscious Billie back to his home and dump him on his doorstep. But, that may have been less out of the goodness of their hearts than removing an unsightly mess from the streets.

The second saloon incident was a couple years later. I was about nine at the time and more equipped to handle it. Like most country boys of that age at that time, I had finally graduated from slingshots and BB guns to a single-shot .22 rifle and I was confident I had the God-given right to shoot any animal in sight.

It wasn’t until many decades later when I settled in my log home, surrounded by a river and acres of forest that I took the time to appreciate animals for what they are and how they interact with each other. Here’s an example. As you might imagine my front yard is a literal zoo full of squirrels. If you have ever watched them you will have noticed that they are intense, hyperactive and driven. Once started on any project it is impossible dissuade them from continuing it. Any home, especially a log home, is a challenge to them because it contains everything they want: warmth, food, security.

After finding my eaves chewed through and squirrels noisily residing inside my house, I decided to take action. I found a nest of them in a partially enclosed area of the roof. I didn’t want to damage the house by firing a bullet into their nest so I used a BB pistol that I have. The shots injured one of them and he ran off, then stopped, came back and picked up his wounded mate in his teeth and carried her over the roof to some trees on the other side of the house. To me, that was the ultimate in courage. While I would have expected it in humans, it absolutely floored me in animals. I never shot another animal. As for the squirrels, I nailed heavy gauge wire screens in all of the spots where they would try to chew through.

The long-barreled .22 Remington that I had as a kid was actually taller than I was and a bit heavy to hold in bony arms, but I considered myself a good marksman. I had figured out on my own the proper alignment of the target’s placement in the front and rear metal sights to make an accurate shot. Of course, it didn’t always work out that way, but it happened often enough to give me confidence in my ability to hit what I was aiming at.

I remember a significant feat, or so I thought at the time. I was at the far end of my grandfather’s farm when I saw a very large jackrabbit about fifty yards away bounding off in the direction of some pines. I snapped off a quick shot and the rabbit did a cartwheel. (I know, it was a thoughtless and unnecessary destruction of an innocent life, but tell that to a country boy back then.)

Or, try telling any country-born man he doesn’t have both the Constitutional and God-given right to own weapons of some kind. Before an assignment to Vietnam in the late sixties, I attended a course at the Foreign Service Institute in the old FSI building in Rosselyn, across the Potomac from Georgetown. The instructor that particular morning was Hermann Kahn, owner and principal guru in his own New York think-tank. Somehow the discussion turned to gun ownership, I suppose because we were all slated to go to Vietnam where guns were a way of life or death. He asked how many people in the group opposed private ownership of guns? About half the class raised their hands. When he asked how many favored gun ownership by individuals the other half raised their hands. He then asked which students were born in the city and which in the country? The country-born, as you would have concluded by now, were the ones rabidly in favor of individual gun ownership.

Anyway, I dragged this rabbit back home. It made quite a picture, since both the rabbit and the rifle were taller than I was. Expecting high praise, I left it off at my grandfather’s place with the expectation that he would clean it and grandmother would cook it. Actually, I learned later that it was buried because they suspected it might have tularemia, a disease common to rabbits at that time.

I might mention that I did have one initial problem in learning to shoot a rifle. I am left handed. I will explain to those who are not left handed what the problem was. The bolt or the mechanism for chambering a round is located on the right side of a rifle. A spent cartridge is also ejected off to the right after it has been fired. This is perfect if you are right handed since you place the butt of the stock against your right shoulder, place your left hand under the barrel, squeeze the trigger with a finger of your right hand after aiming with your right eye. After firing, you do not need to remove the stock from your shoulder because your right hand is free to open the bolt then slam it forward, chambering a new round. If you are left handed, none of this works.

Early on, my brother Art noticed I was firing left handed and decided I needed to change. Initially I was reluctant, but he pointed out that if I ever went in the Army I would have to shoot right handed. That did it. I imagined myself a future Sergeant York or some other Medal of Honor winner. Back then, being left handed had many draw backs. In school, my teachers tried to get me to write with my right hand (like everybody else). I did, but what I wrote came out upside down and backwards. They quickly allowed me to return to being a lefty, no doubt worrying that they were dangerously disturbing the circuitry in my brain.

But, back to the saloon incident.

The second saloon incident involved a drunken ‘Finlander’ from the neighboring village of Wolf Lake—a village populated almost exclusively back then by immigrants from Finland. This was on a weekend late in the evening. Even I could see that when this man came into the store he had been drinking heavily. He looked around, saw nobody there except my mother standing behind the counter where the cash register was. I sensed immediate trouble.

To this day, I don’t remember if an actual word was exchanged between the man and my mother. I was totally, 100 per cent concentrated on just two things: The proximity of the knife he was holding to my mother and the alignment of my .22 sights on the center of his forehead. All I know is that once inside he moved quickly to the counter and picked up one of the long, very sharp butcher knives that my mother used to slice meat for customers. As he moved toward her he held the knife in front of him in a thrusting position.

I was at the end of the room behind a large stack of fifty-pound flour sacks. At that time, flour was often sold in large cotton sacks which country women would then launder once the flour had been used up and sew into shirts or dresses. With me behind the barricade of sacks was my single-shot .22. I quietly raised it, resting it on a flour sack, and took aim. I knew I had only one shot and if it missed, the man with the knife would be on me. As he moved toward my mother, I kept the sights on the exact center of his forehead, my finger firmly on the trigger. Of course, I did not want to shoot until I actually had no other choice. I reasoned that once he had reached striking distance of my mother I would have to pull the trigger. He moved behind the counter. My mother was frozen in place, terrified. Just as I was about to squeeze off the shot that would kill the man, my mother turned and ran out the back door. The drunk stood there for a moment, then dropped the knife back on the counter, returned to his senses and left by the front door. I’m sure he never realized how close he had been to death.

Later when my mother came back in the store, I told her she didn’t have to worry because I had everything under control. I remember what she replied, “oh, I wondered where you were.” That was it. The incident was never mentioned again. Nor to my knowledge did she ever tell anyone else about it. It wasn’t the kind of thing ladies talked about.

Fortunately, the following year the bar owner found a better location in the Finnish village of Wolf Lake and Osage became a less precarious place to live, I thought, at least for the time being.

One morning at about seven thirty as my mother opened the store, to her amazement she found it had been broken into. There was a small room at the back of the store, empty except for a light box where she carded eggs bought from local farmers. Each egg was placed over a bright light to make sure that it didn’t have little chicken embryos inside the shell. In the back of this room was a single sash window and it had been shattered and then opened. To keep the noise down, the thieves had tacked an old blanket over the window before breaking it.

Since my mother always took the money from her cash register home with her at the end of the day, all the thieves took were groceries, mostly canned goods—probably provisions to feed a hungry family. Anyway, from then on, my brother Art slept in the store’s back room with his pump 12 gauge shotgun. I think he probably enjoyed both the isolation and the adventure.

As I mentioned, my mother always took the cash box home with her when she closed the store at eight p.m. Though it was just a short distance to the house she was almost always accompanied by Pal. Pal was a very large German Shepherd belonging to my uncle, the garage owner. Pal would dutifully walk her home. Then wait outside while she went in the house and then amble back to wherever he slept in the garage.

Sleeping was actually one of Pal’s favorite pastimes. I remember during one hot summer day he made the mistake of sleeping in the shade under my grandfather’s Model T Ford. Without looking around, my grandfather cranked up the old Ford climbed in and rolled right over Pal who indignantly got up, shook himself off and found another place to relax.

This was now at the height of the depression and times were getting desperate. They were especially desperate for grocery store owners. It was a small town. You knew everyone there. They had been your customers and neighbors for years. Now they needed credit just to buy the family essentials. Unfortunately my mother couldn’t restock her shelves without paying cash to the jobbers that trucked in the supplies she needed. They wouldn’t extend credit. Somehow she managed to offer credit to those that were most desperate, forgo profit for herself, and buy what she needed from the jobbers so she could stay in business. This went on for years.

Incidentally, everyone was grateful, but not so grateful that when jobs again became available in the 1940s that they made an effort to pay their long past due bills. She ended up losing thousands of dollars. To add insult to injury, in the early forties she decided to have her own house built on an acre lot she bought on the south edge of Osage on a hill overlooking Straight River. She asked various men who owed her money to work on the home. They all declined because they claimed to have other jobs they had to do. She ended up selecting a Cape Cod style house from an architectural plans catalog and hiring a local contractor to build it. He did a good job, but built it two feet shorter in length than the plans specified, thereby making a little extra money for himself. The moral of that story is that being a woman in business back then did not inspire much respect.

To my surprise one autumn day during the depression a large canvas covered truck rolled into town with baskets of red delicious apples to give away. The news spread quickly and people lined up behind the truck to get the free apples.

Another day, the Baptist church received a truckload of used clothing to give away to poor people. I certainly hadn’t expected anything because I didn’t see ourselves as being poor. However, the preacher brought over a bright, multi-colored flannel bathrobe that fit me. I was immediately taken by it, though I felt guilty that it didn’t go to someone more deserving.

My grandfather in his early days in Osage had also been a store owner, though the first one back then was called a trading post. Heated by wood-burning stoves (as was my mother’s) it caught fire and burned down. He built another in 1890. Same thing happened. In that case, hamburgers were being grilled for a town picnic behind the store when some grease caught fire and burned it down. After apparently building a third one he went out of the store business and sold it to a neighbor.

My grandfather built a large, and quite sumptuous two-story frame home, with three wings, cross-mullioned windows and a long, open porch with carved columns rising from the floor. He had reason for it. He had three sons and three daughters, a mother-in-law, her husband, and her brother living with them, along with his own parents. They all lived and worked on the farm until the elder relatives died, the three girls got married and moved off as did two of his boys—one to Idaho to later be in charge of the state’s forestry service and the other to San Pedro to work in ship-building. The third and youngest, George, was designated to one day inherit the farm and to take care of the surviving family members. It was the kind of social insurance all families of that economic class in that day and age depended on for survival in old age. Unfortunately for my grandparents the younger son, George, died of a heart attack long before his parents did.

By the time my mother separated from my father in Charlotte, North Carolina, and moved back to her family in Osage with my brother and three sisters, my Grandfather’s house had plenty of vacant rooms. By the way, my mother was pregnant with me when she left Charlotte so I can say I was conceived in the South and raised in the North. Does that qualify as being multi-cultural?

I don’t know whether my grandparents were happy or not with this incursion into their life that had for the first time in their marriage just involved the two of them. I am quite sure the next tragedy that struck them would definitely not have been a cause for celebration.

In 1929, fire struck again. My grandmother, as was her habit was baking quantities of bread and cinnamon rolls when sparks from a faulty chimney set the house on fire. Everyone’s main concern was getting valuables out of the house before it burned to the ground. It wasn’t until the fire was well underway that my older sister Florence asked, “where is Tommy?”

Less than two-year old Tommy was upstairs in his crib about to be barbecued when someone rushed up and carried me down. All of us then spent the winter in a rundown old hotel that had been built during Osage’s logging days and was now, thirty years later, mostly unused and decrepit. The following year, my grandfather built a smaller four bedroom house on the site where the old one had once stood. The exterior of this one was covered with stucco and less likely to burn.

My grandparents and their relatives were the first white settlers in the area. My grandfather, Arthur Wellington Sanderson, was born in 1859, inadvertently in Canada. His father lived in Massachusetts and had a flour mill. He often carried the flour across the border into Canada to be sold. On one such trip with his pregnant wife along, my grandfather was born and thereby became a Canadian citizen.

While still in his twenties he took a boat west from Lake Erie to Lake Superior where he went by saddle horse down to the southern Minnesota town of Austin. He would have gotten to Lake Erie via the Erie Canal which was completed in 1825, and traversed the 363 miles from New York to Buffalo. The trip by flat boat would have taken five days and cost a penny and a half per mile. In Austin he met my grandmother, Mary Adeline Bullock, the daughter of a store owner.

In 1879, at the age of 21 he joined three other pioneers who were exploring what they called the Third Prairie, and later Shell Prairie, in Northern Minnesota, with the idea of staking out homesteads there. It was an area of blue stem prairie grass, interspersed with white pine, jack pine and spruce, along with oak and other hardwoods. The prairie grass, with the aid of horse and plow, could be uprooted into fields for the profitable wheat production as a cash crop. By the 1900s, Minnesota wheat production reached 95 million bushels.

The Homestead Act had only three minimum requirements: The family must clear an acre of land. They must construct at least an eight by ten building with a floor, a door, a window, a stove and a bed, and lastly, pay $1.25 per acre. A quarter section of land amounted to 160 acres and a section was one square mile. A township was six square miles. The village, later named Osage was located in what was later to be called Carsonville Township.

With homesteading in mind, my grandfather found what to him seemed to be the ideal spot for a family farm on the edge of what is now named the village of Osage. Osage, by the way, was not named after the Osage Indians who lived several states to the south of Minnesota. It was named after a man named O. Sage, who had a town in Iowa named (Osage) after him. Being rather well-to-do Mr. O. Sage reciprocated the honor by donating a substantial amount of money to the town. The namers of our village of Osage (rest assured not my grandfather) apparently hoped the good natured Mr. Sage would make a similar donation here. He didn’t.

My grandmother, born in 1860, remembered her parents had taken her to the mass hanging of 38 Santee Sioux Indians that had allegedly taken part in the massacre of over eight hundred white settlers in Minnesota.

In 1862, the Santee Sioux Chief, Little Crow, went to the Indian Agency on the Minnesota River reservation, after giving up their twenty-four-million-acre hunting ground ten years earlier. The chief asked that the stockpiled provisions be distributed to his starving band. The agency’s trading post operator replied, as far as he was concerned “they could eat grass or their own dung.” A few days later, the trading post’s operator was found dead with grass stuffed in his mouth. The provisions and money due the Indians never seemed to get through the graft-ridden Indian agency.

The Indians decided they had finally had enough and with Union Forces heavily engaged in the Civil War, they felt the time had come to take back their land. It was not a well-timed rebellion. By early fall, troops had been rushed to the area and the insurrection was essentially over. Some two thousand Indians were captured and each tried in ten-minute trials. The military board sentenced about four hundred to be hanged and the list was sent to President Lincoln for approval. He was aghast at the number, sure that if he approved it he would go down in history as a butcher of Native Americans. Sensibly he sent a board to review the trial procedures. They came back with a list of only two to be hanged. Knowing this would not be enough to appease the relatives of the eight hundred whites that had been killed, he asked for another review. This time the list to be hanged was thirty-eight. All at one time on a giant scaffold, singing the same war chant as they plummeted to their death, as witnessed by my grandmother.

The area, that is now called Minnesota, was first acquired by Britain in the late 1700s and then by the U.S. after the War of Independence. It received the status of a territory in 1840 and was admitted to the Union in 1858, a few years before the Civil War. By the early 1880s it was the world’s largest flour producer resulting in a railroad track halfway up the center of the state to the town of Verndale to carry the product to market. Some of the best soil for wheat production, a rich, fertile loam, was deemed to be on the three Shell Prairies. The first of these was located around the present village of Hubbard. The second in the farm land around Park Rapids, and the third in the vicinity of Osage. All three were part of a high plateau formed by a retreating glacier some 11,000 years ago.

No doubt you’ve heard friends say from time to time that they wish they could return to simpler times. Really? All I can say about that is be careful what you wish for. God help you, it might actually happen.

I remember in the dead of winter seeing my grandmother on the open back steps of her house crouching over a steaming tub of sudsy water wringing out my grandfather’s shirts and then diligently scrubbing them with yellow bar soap and a hand brush against a washboard to get them clean. Once clean, she would use clothes pins to hang them on the outside clothes line. Then, as soon as they were frozen solid she would shake off the ice and bring the dry shirts inside the house to iron with flatirons that had been heating on the top of her kitchen wood stove.

By the way, the hot water in the wash tub didn’t come from a water heater and then through a tap. There was no indoor plumbing. It came from a small hand pump in the kitchen where it was caught in a pail and then dumped into the reservoir of the kitchen stove, an oblong, zinc-lined, cast-iron box that was heated by the fire in the stove as it passed under the box and out through the chimney.

Grandmother had a constantly, 24/7 busy day as we would now say. She cooked the meals over a wood fire or in the stove’s oven. Served them on sparkling English china. Washed them in hand-pumped water and then towel dried them.

My grandfather always kept three or four Jersey cows, those being the breed he preferred because their milk was high in butterfat. Having finished hand-milking the cows he would bring the pails of warm milk into an alcove off the kitchen where he had a separator. The separator had a bucket-shaped protrusion on the side with two spigots, a long-handled crank and a gear arrangement that increased the speed at which it could be cranked. When in use, it made a high speed whirring sound much like an airplane propeller. My grandfather would very energetically crank the separator and the raw milk would spin at high speed causing the yellow cream to come out one spigot and the thin, bluish-white, fat-free milk the other. The latter was considered unpalatable and given to the pigs. Grandmother received the cream in her butter churn. The churn was a heavy stoneware pot in which a wooden paddle was pumped up and down by hand until the cream was turned into butter. This was neither a quick nor easy process. The lump of butter was then placed on a plate and kept in a cool area of the basement where it would remain fresh for a few days.

Preserving food was a big chore back then. My grandmother kept a huge garden. There was row after row of sweet corn, with pumpkin and water melon vines between the rows. Cucumbers, snap peas, carrots and huge bushes of tomatoes, lettuce, onions and cabbages were surrounded on each side by root vegetable like potatoes and turnips.

After harvest, all of these had to be somehow stored for winter use. The root vegetables were kept in an underground root cellar. This was a fairly shallow dug-out cave deep enough in the earth where the potatoes, for example, wouldn’t freeze in the winter.

The above ground vegetables for the most part were canned. Not at all an easy process. The jars and lids had to be boiled for at least twenty minutes to sterilize them as did all the knives, spoons and ladles used to prepare them. The vegetables were then cooked, boiled or steamed in their individual pots and ladeled into the jars. The tops of the jars were sealed with melted wax and then the lids were screwed on tightly and taken down to shelves in the basement. Cabbage was usually made into sauerkraut where it and its juice were placed in a barrel in the basement to keep it from spoiling. Berries and rhubarb, locally called pie plant, usually underwent the canning process, though often times strawberries and raspberries were also made into jams and jellies.

Winter storage of meats presented definite problems, with only partial solutions available at the time. The most common solutions were either smoking or salting. My grandfather had a smokehouse where he would hang hams, filleted fish, and dressed poultry. Chunks of salt pork were kept in a big wooden barrel in the basement. The pork chunks, which tended to float in the thick brine, were kept underwater by a heavy wooden lid weighted down with rocks to the point where it would the pork chunks submerged in brine.

Of course, every family farm had a chicken coop and a chest-high wire enclosure where the chickens could go out during the day and scratch around for cracked corn scattered in their pen area. The coop had individual nests for each bird and it was necessary to take out the eggs each day. Older hens that were no longer good performers usually ended up in the Sunday oven stuffed with wild rice and sage and bubbling in a stoneware pot of chicken gravy. Chickens were usually herded back into their coop at night so that foxes and coyotes wouldn’t be able to burrow under the wire and grab some of them. Eagles were the chief daytime scavenger to beware of. Why the eagle was adopted as an American symbol I will never know? In real life, they are truly nasty birds, with the ugliest screeching voice this side of hell, and a menace to every small animal and bird on the face of the planet. Pioneer farmers, of course, recognized them for what they were and shot them on sight.

I’ve always thought the American bison to be a far better symbol. It’s unique to our hemisphere and distinct by its shoulder hump from the buffalo, which is a sometimes domesticated animal in the Far East. The bison is aggressive only when threatened and then bands together in a group to protect all of its members. A far more admirable trait than the predatory eagle that snatches an animal up from the ground carrying him up for a hundred feet and then dropping him to his death, where he can pick over the shattered carcass at his leisure.

Sunday dinners at my grandparents was definitely an occasion you would remember. First, it was served on a large, round oak table with insertable leaves to stretch the length if needed. The dining room was located in front of a south bank of windows where ferns and various flowering plants were grown. In front of one of the windows was a canary in a metal cage. The dishes were kept in an oak china closet with a curved hand-blown glass front.

The usual Sunday fare was a well-browned very large and plump chicken to be carved by my grandfather, mashed potatoes to be served by my grandmother, gravy in a gravy bowl to be passed around the table, freshly baked buns and buttered peas. My grandfather, in English style of the day, used his fork to balance the peas on his knife and eat them that way.

Freshly made pie followed the main course accompanied by hot tea in fine porcelain cups. My grandfather usually cooled his tea by pouring it back and forth between the saucer and his cup, this being more refined to him than blowing on it.

Of course, before anyone set about to eating there was a silent prayer with bowed heads and down-turned eyes. Fortunately, the prayer was brief since no one wanted the blessed food to get cold.

That was Sunday. The daily meals were not quite that extravagant, but still would raise a few eyebrows by present health recommendations. Breakfast (6 a.m.) was slices of salt pork fried a crisp brown in their own grease in a cast iron pan, eggs fried in the same lard, fresh bread warm from the oven with a thick layer of homemade butter, homemade jam or jelly, coffee with sugar and heavy cream. Lunch (noon) would include fried, roasted or baked meat, cottage fried or mashed potatoes and gravy, canned or fresh vegetables depending on the season, tea with sugar and cream, and a dessert of pie, cake or pudding. Dinner (6 p.m.) would have been a variation of lunch. Before you cast too many aspersions on their menu, please bear in mind that neither of my grandparents were overweight, never took supplements or vitamins, and to my knowledge they never had any protracted illness nor had reason to visit a doctor. Both lived into their late eighties. However, bear in mind that their diet did not include any present day food additives, preservatives or chemical taste enhancers. There were no frozen food dinners with a list of chemical preservatives an inch long on the back. Fresh vegetables and fruit came from the garden and hadn’t been sprayed with insecticide and sealed against the elements with wax or plastic spray. Bread was from wheat they had grown and milled and had never been whitened by bleach or had its freshness preserved by chemical additives.

My grandparents moved to their new homestead in 1880, the year after his exploratory journey, to the area that became Carsonville Township and later Osage. The trek from Austin, Minnesota, brought all of their possessions in a covered wagon along with a herd of milk and beef cattle, saddle horses, pigs and chickens. Accompanying them were Mary’s parents, Cyrus and Sarah Bullock, and Cyrus’ brothers Lemuel, Azuba and George. My grandfather’s parents also came along, Arthur, Sr. and his wife Hannah (Graves).

One of the things that slowed them down was that my grandmother had brought her cat who gave birth to a litter of kittens on the way up. The kittens had a habit of wandering off and the mother cat would then disappear in a search for them. Apparently, grandmother wouldn’t leave until the cat returned. My grandfather who hadn’t yet married her was probably overly tolerant of the delays.

Eventually they made it to the area that my grandfather had claimed the year before. Farmland with the richest soil. The choice was immediately to the west of what later was dammed up to became the millpond of Straight Lake but was at that time a river at the outlet of the actual Straight Lake. Incidentally, pioneers did not at that time want their claims to back up against lakes or rivers because part of their acreage would be underwater and unplantable for crops.

To be self-sufficient back then, a family farm had to include a certain number of acres of forest for heat, cooking and lumber, a pasture area for grazing livestock, and a tillable area for crops such as wheat, oats and corn, plus high and dry sites for home, gardens and outbuildings.

My grandfather had built a rather primitive log cabin the year before. This would get them through the first winter and give them time to work on the permanent house, barn, chicken coop, woodshed and pig pen. None of this would have been an easy job. They had to cut their own logs. Then it would have required hand saws to cut the lengths of logs into boards of the right thickness, and hand-plains to smooth the surfaces.

Nails back then were made out of unplated iron and the heads tended to rust off if not covered against the elements. So, where ever possible, the prudent builder used wooden pegs to hold boards against rafters and studs. Joints of the heavy support timbers were generally sawn and morticed so they could be wedged into a tight, permanent fit.

Shingles were cut from blocks of wood with a chopping axe. In other words, houses, barns, sheds, pens and wooden rail fences were all laboriously hand-hewn. Unfortunately, so were stone and brick chimneys and fireplaces, and when cracks developed because of loosened mortar, sparks came through usually into an adjacent wooden area that had been dried from heat due to the proximity of the chimney. The result was usually total calamity because there were no fire brigades and only a nearby well to slowly fill buckets to douse the flames.

Cutting trees for the winter heating supply of fuel was an onerous task. Normally the trees were cut down with a heavy double-bitted axe—that means one axe head with blades on both sides. When one dulled, you shifted to the sharp one. When both were dull, you needed to either bring out the file or take it back to where you had the peddle-operated grind stone.

Once the tree was down, you were left with the job of trimming off the branches and using a cross-cut saw to cut it into blocks. If you were lucky enough to have an available partner, you would put the log on a sawhorse and each of you would grab a handle of what was sometimes called a Swede saw and while one was pushing the other would pull. The cut wood would then be loaded onto a sled and a team of at least two draft horses would haul it to the woodshed where your next job was to use a single-bladed axe with a hammer type protrusion on the other side to split it into halves or quarters. The hammer head opposite the axe blade was used to drive a wedge into a partial split where the block was often kept from falling open by a crossgrain or tree limb sprouting from the interior of the trunk.

By the time I was of an age to be of any use to my grandfather, he had bought a one-cylinder gasoline powered engine with a large flywheel. The cast iron flywheel was of a heft that once started turning in its circular motion it was heavy enough to continue its momentum with the help of the small engine. This was all mounted about knee height on a heavy plank table. On an axle extending across from the flywheel was a circular saw about three feet across. The log was then lifted onto the table in front of the whirling saw blade and pushed against it quickly cutting the log into blocks of the desired size.

When I was a kid, Osage was a town of many widows, so it was customary in early fall to assemble saw gangs—people who were available to do a little free work—and cut the winter’s supply of wood for the widowed ladies. I remember one time we were at a ramschackle old place near the mill pond and across from the grave yard. (Incidentally, my grandfather had also donated several acres of his property to the village for a community graveyard with the proviso that specified plots would be left vacant for his descendants. Do I need to mention that later graveyard custodians sold off many of the reserved plots.)

Anyway, we had just started sawing logs when the engine began sputtering because it was low on gasoline. The person who owned the rig unscrewed the gas cap and began pouring gas into the overheated engine while it was still running. He wanted to keep it running so that he wouldn’t have to bother with starting it up again. Not surprisingly, the thing caught on fire. There was a strong likelihood that when the flames got into the confined area of the gas tank that it would explode in one huge ball of flame. Everyone ran. I ran up to the engine, grabbed the gas cap and quickly screwed it back on. Shortly, the flames died out and we continued cutting wood. Probably because they were embarrassed by running off instead of trying to handle the situation, no one said a thing to me about it. We just finished our job and went home.

I have found numerous times in years since, that when confronted with a potential catastrophe, people often visualize the worst case scenario and panic into taking a senseless action. I remember one vivid example of this from my first winter in Korea. I went back from the front line where the battalion was situated to a rear area about two miles back where the administrative and logistical units were located. Apparently the Chinese had somehow found out the coordinates of that unit and they were literally raining artillery shells on the area. I had my driver take the Jeep elsewhere and then I walked over to about a football field size area that the Chinese had zeroed in on. There were twenty, or so, soldiers flat on the ground trying to hug themselves into depressions that might protect them. This was exactly the opposite of what they had been taught to do. On sporadic artillery fire it’s safest to hit the ground and move on when it is lifted, but on sustained fire you should move out to another area because sooner or later some of the rounds are going to be right on top of you. I yelled at them to get up and move. They didn’t, so I walked out in the area and looked at each one and told them to move out. They could see I was standing up unhurt so they did it. (By the way, this was not a heroic act on my part since I don’t happen to be frightened by artillery fire.)

Machinegun fire. Well, that’s different. Less you think I’m some super cool tactician, this will set you straight. I used to send out heavily armed patrols to probe far enough ahead of the lines to see if they drew fire. Often they did.

However, sometimes I would go out on patrol by myself just to see what I could see. I remember one afternoon I went forward from a company position and wound my way down from the hill where they were located through their barbed wire and minefields, until I came out on some flat, brushy land that offered some concealment if you stayed in a crouch. I traversed back and forth a mile, or two, forward, but didn’t see anything of interest. Since it was getting late, I started back only to find that by the time I reached our lines it had become a very black night. Somebody on the hill heard me thrashing around beneath them and assumed it was an enemy patrol, so they opened up with everything they had, including machineguns—which made the hair stand up on the back of my neck. I was carrying a Thompson submachinegun at the time, but I obviously couldn’t shoot at our own soldiers, so I hugged the ground until they stopped firing and then called up to them. Since I also didn’t know the password they were using that day it took a bit of negotiating to be told the path I needed to follow through the minefield. I still have an occasional nightmare about that. But, enough with war stories.

Late in the winter, usually about mid-February, ice-cutting crews would be formed. They would clear the snow off an acre, or so, of the lake and use long, ragged-toothed saws to cut the ice into blocks about a foot-and-a-half square. By that time of year, the ice was about four feet deep so the single rectangle of ice would weigh about 40 pounds. It was lifted out with ice tongs and loaded onto a horse-drawn sled. The blocks were stored in ice houses with each layer of ice covered with sawdust and the next layer piled on top all the way up to the roof. It was then up to the owner of the store, or user, to drag out a block of ice each day, chip it into flakes and place them in the ice box with coarse salt to cause the ice to melt and increase its coldness. This was one of my mom’s morning tasks until FDR’s New Deal and the resultant rural electrification program came along in the late 1930s.

Blizzards were a real concern back then and God help the family who hadn’t stockpiled enough nearby wood to last at least a week while the male members of the family dug them out. I remember one blizzard so bad as a kid that my grandfather had to string a rope about the length of a block from his back door to the barn where he had to go each day to tend the horses and cows. Without the rope to guide him, he might have lost his way.

Once as a seventh or eighth grader I had run a trapline for several miles along the lakeshore in the hope of catching a mink whose pelt would have brought me the unimaginable sum of about $20. (Have no fear animal lovers, I was never that skilled a trapper.)

Anyway it was a cloudy, blustery cold day when I started out for the last three miles to home. Within a half hour my worst fears were realized, I was caught in a blizzard with snow so thick and wind so strong that I couldn’t see my own feet. There was no possibility of seeing any landmarks. Fortunately, I usually carried a walking stick to push snow-covered brush aside in forested areas. With my pocket knife, I sharpened one end of the stick so I could punch it through the snow and that way tell whether grass was under the snow or a hard surface. I knew direction, more or less, from the constant direction of the north wind. When it was driving against my back that meant that I was headed south—the general direction of home. I also knew that if I continued south, sooner or later I would find a road. I wouldn’t be able to see the road because there was zero visibility along with the heavy snow layer covering the road, but by using the pointed stick I would be able to tell the hard surface of the road from the grassy surface of the fields. Stumbling along for two or three hours I finally made it back to Osage. No one had missed me, since I was usually off somewhere by myself.

I used to like to tramp off into the woods by myself. Once, in late November I took my rifle and sleeping bag and headed off into what was called the Smoky Hills west of Osage. From a distance they did at times appear to have a smoky haze along their ridge lines thought somehow to be caused by the heavy iron deposits under them.

The area I chose that day was a swamp heavily forested with fir, spruce and tamarack with moss hanging from the branches to the ground. Being early winter, the swamp was completely frozen so it was possible to walk through it. That evening, I found a small opening next to a spruce tree whose limbs draped down in an almost tent like covering. There I rolled out my sleeping bag, leaned my old lever action .44-40 rifle against the base of the tree and bedded down for the night. It had snowed lightly during the night and my sleeping bag was further insulated by a covering of snow. When I awoke in the morning I had an eerie feeling. Things were just too quiet. There should have been squirrels chattering and birds chirping. There should have been movement. Nothing! But, I sensed there was something.

Without moving my head I shifted my eyes until I caught a slight, but totally silent blur of movement. It was a silver gray timber wolf and he was slowly circling around me to see if he could get close enough to attack. As I watched him, each circle brought him closer in. By the time he was about 20 feet away I reached for my rifle and he was gone so quickly and silently that it seemed he had never been there. It left me with an odd feeling, for once to have been stalked by a beast intent on eating me. With the tree-draped moss and the pristine blanket of snow it was if I had been transported back to prehistoric times.

At that time, neither the wolf nor I knew that he would most probably have been in no danger from the rifle. The rifle was bought some years before by my brother from a used dealer. My brother then set about restoring it. He first made a shallow wooden trough and filled it with a bluing agent, and then placed the barrel in it for a couple days so the bluing would adhere and keep it from rusting. He also did some filing and oiling until he got the lever and trigger mechanism operating in a satisfactory manner. The rifle and the black powder ammunition that came with it were manufactured sometime in the 1880s. Locally, the .44-40 caliber was considered a good brush gun because it had a rather low velocity and a heavy lead bullet that was thought might not be knocked out of its aimed trajectory by brush or tree limbs that might be in the way.

Anyway, while my brother was away working in the Alaskan gold mines, I inherited the rifle and the ammunition. At the time, nothing would have brought me more pleasure than felling a large buck with a rack of antlers that I could display to one and all, and of course, presenting my mother with a couple hundred pounds of venison.

Shortly after the encounter with the wolf I chanced upon a huge buck with a really memorable rack. It was late in the evening and he had his head down eating grass that he had scraped from the snow. I was probably within 50 feet of him and at that distance could have hit him with a rock. I took careful aim and fired.

I might mention that at that time in Osage people were not particularly concerned about hunting licenses or hunting seasons. I know, in my own case, I never bought a license and didn’t even know where one would have to go to get one. As for hunting seasons, it was anytime in the fall that you chanced on something that was edible.

Anyway, I fired the old rifle and it made a suitably loud explosion with enough noise and smoke that it caused the deer to look up. Seeing me it shook its head and majestically trotted off into the brush. I was totally mystified. I absolutely knew that I couldn’t have missed a target as large as that buck from just 50 feet away. Yet, the bullet obviously hadn’t even come close enough to put a scratch on him.

Back home, I explained my befuddlement to my mother. I’m sure she thought either I took faulty aim or got ‘buck fever’ and intentionally missed. An hour, or so, later while cleaning the rifle with a ramrod the mystery was solved. On the first pass through the barrel, the ramrod poked out the lead bullet. The black powder was so old that it didn’t have enough explosive power to push the bullet through the barrel. Fortunately for me, I didn’t try a second shot because if that shell had been okay it would have struck the bullet in the barrel and blown the whole thing up in my face.

Of course, the story about the wolf now always reminds me of the parable of the two wolves. Not the one my philosophy teacher referred to about the wolf cub growing up with lambs, but an older one from village folklore that is more appropriate to a class in behavioral psychology rather than philosophy. Perhaps you’ve heard it?

A boy dreams of two wolves fighting. One a jet black wolf and the other silver gray. Night after night in his dream the two wolves tirelessly lunge and slash at each other. Finally, tired from his sleeplessness, the boy asks his grandfather: “Which wolf wins?” His grandfather replies: “the one who wins is the one you feed.”

Wolves are often omens, symbolizing good or evil.

I was happy one evening when looking over the property here on the bend of Straight River where Christine and I were to eventually build our present home, to see the almost ghostly shadow of a silver gray wolf move as quick and silent as a dream along the edge of the tamarack forest to the west of our building site. It was the good wolf, the one I hoped we would feed.

As a kid, I came down with scarlet fever. I remember for several days my mother kept me in bed in a darkened room. Apparently, this was thought to protect your eyes. Of course, there was no doctor, nor any useful antibiotics at that time, so rest was the only remedy. But, I remember Art, who was a very skillful hunter, came back with a tiny wolf cub that I was able to play with on the bed. However, that didn’t last for long. All I knew at the time was the wolf cub was gone. Unfortunately, permanently gone, since there was a bounty on wolves.

There was only one time that I can remember that I managed to get the better of Art. We were walking along Straight River. He had just bought himself a semi-automatic .22 pistol. Along the bank of the river, he saw some large icicles hanging down over the water. He fired several shots at one particularly large icicle, but missed each time. When he put in a new magazine, I asked if I could try it. I lifted the pistol. Did a quick aim and fired. The icicle shattered. He took the pistol back, but did didn’t say anything. As we went farther along, he scolded me for making too much noise as I walked. For the rest of the walk I had to carefully put my toes down first and then quietly lower my heels to keep from making noise.

I hope you don’t mind skipping back and forth in time? As you have probably become aware through your own experiences, all time is conjoined. The past is baggage carried into the present and the present is irrelevant without the hope a future offers.

Of course, there eventually comes a time when the future isn’t there for you. That’s when you write memoirs like this.

By the way, before I proceed further, I think I need to rectify a wrong impression that I may have inadvertently given about myself. If upon reading all of this you have somehow been led to surmise that I was this easy to get along with Tom Sawyer kind of a kid that didn’t present problems to other family members, then it’s probably time to set the record straight. I was a total, self-centered little brat that no doubt taxed my mother to the very limit of her patience. She, for some reason unknown to me, never once scolded me or God forbid actually struck me though I’m sure it would have been a relief to her to have done it. Let me explain.

I do remember though, once I was in the kitchen while she was doing the dishes. And, as usual, I made some smart mouth comment while she was standing in front of me with a wet dish rag in her hand. Before she could stop herself she flipped the wet dish rag across my mouth. Instantly she looked stunned that she had done that, then shocked. I was momentarily, for once, speechless. My mother, I could see, was astonished by what she’d done. I laughed, knowing I had truly deserved just what I got. She found a dry towel and wiped my face.

I think my mother saw my fractious nature as a problem she had created by separating from my father. Strangely enough, the only time my mother ever mentioned my father to me was when she said that she didn’t know whether or not she’d done the right thing by depriving me of a father. I think her presumption was that a father would have been better able to handle me.

I had no doubt that was true, because all of my young friends had fathers who were real disciplinarians—with woodsheds and leather razor straps that could raise a few welts on their deserving behinds. Needless to say, I was perfectly happy to live without that kind of parental guidance.

Also, how could you miss what you never had. It was simply not possible to bond with someone you’d never met. I have no doubt that my brother and sisters missed him. I think Grace, in particular, would have been more content with a genteel life. A very beautiful young lady, she liked to dance and dress up in her best clothes. She was probably the quietest and most introspective of all of us.

My father, because of his service in the two wars, was buried in the national cemetery in Chattanooga, Tennessee. One time when I went down to Asheville, North Carolina, to visit my daughter, Sara, who I had sent to college near there, we drove up to Chattanooga and found his grave marker. That, I suppose, was a close as I ever got to my dad.

Often in Osage when I was a kid I would go up to the post office where Art Sartain was the post master. He had the mail boxes on one side and a small grocery store on the other. Our box was No. 105, but I’ve since forgotten the dial combination lock numbers that would open it. Anyway, Mr. Sartain had a long wooden counter at the other end of the store, next to a wood-burning stove. On the counter there was always a checker board with a game in progress. While there may not have been anyone actually playing checkers at the time, the pieces were placed where the last move had been made. Even though I was too small to play, they never minded that I would sit up on the counter and watch the moves that each of them made and, of course, listen to their often irreverent conversations.

In the summer time, in addition to checkers, the men would meet outside the store where they had a horseshoe pit. These games would go on for hours. Often, Fred Bateman, who lived in the house next door to the post office would come over to join in the games.

Fred’s wife, Jennie–crippled and in a wheelchair–ran the Osage telephone exchange. It was a large console with a battery of receptacle holes in it where you would connect the calling party to the number being called by physically pulling a line up and plugging it in. Since these were all party lines, you would then have to turn a crank on the console to make the right number and sequence of rings to get the requested person to answer their phone. To differentiate one person from the several others on the same line, each person had their own rings; for example, it might be something like two long rings, a short ring, and another long ring. Hearing that, the person would answer the phone, of course, so would all their nosey neighbors listen in to keep up on the latest gossip. If I was in their house at the time the switchboard phone rang I would sometimes answer it for her if she was busy in another room.

Fred’s job was to keep the actual phone lines up and running. I would sometimes go out with him and help with this job by putting on climbing spikes and going up a pole to repair a broken line or replace a glass insulator. Winter storms with heavy snowfalls in particular always did the most damage to the lines that were already taut from the cold. There was a trick to stringing lines in the summer. They had to sag just enough so that when they tightened up in cold weather they wouldn’t snap.

But, back to my own family and their problems in dealing with me.

Once, when I was in the front yard with my older sister, Florence, something or another caused me to swear. I suppose I said “dammit” or something rather tame like that. She grabbed me, took me into the kitchen and actually washed my mouth out with soap. It didn’t stop me from swearing, of course, but made me cautious enough not to swear in front of her.

Florence had great hopes that I might turn into a proper gentleman. She never gave up on those hopes. I remember once years later I had made a trip out to Spokane where she was living. Of course over the years I had sent her photos of me from where I was living in Washington, D.C., so she knew I had grown a beard. However, she presumed from the photos, I guess, that it was a goatee of the type a professorial gentleman might be expected to wear. When she saw me in person and could see it was just a scraggily beard, she registered disappointment on her face, accompanied by a remark that she wished I would get rid of the beard.

Since my mother was tending store before I got up in the morning, my sister Eleanor was usually saddled with the job of making my breakfast. This, as everything else with me, was an ongoing battle of wills. I would have been happy to eat a Milky Way at breakfast, but that was never the choice. It was cereal, toast and a large glass of milk. The cereal was usually oat meal or Cream of Wheat. The bribe was a big monthly calendar behind the kitchen table with gold and silver stars on it. The gold stars—very few, if any—were pasted on the calendar when I ate the cereal without creating a problem about it. The silver stars were when after sufficient coercion I ate the cereal.

My other breakfast problem was the glass of milk. I wanted coffee just like everybody else had. In this case, they appeased me by giving me a half glass of coffee with the other half of milk and, of course, a couple spoons of sugar.

That was just the opening battle of the day. Things got worse as the day progressed, so you can see why they very happily let me wander off by myself as often as I liked. Probably thinking the farther the better.

With the election of Franklin Roosevelt, my brother, Art, having just graduated from high school joined the newly-created Civilian Conservation Corps (CCCs) and was sent off into one of the Northwoods tent city camps where they cut fire breaks through the forests. These were 40- or 50-foot lanes cleared of trees and brush so that a forest fire wouldn’t be able to jump from one stand of timber to another. In other words, they were constructed to contain and limit an accidental fire to only one sector of a forest.

No doubt it was hard work, plagued by mosquitoes, biting deer flies, and the ubiquitous woodtick. But, Art liked it and was good at it, no doubt having inherited genes from my father who was a civil engineer.

My dad, Thomas Weatherby Swinson, was born in Nebraska to Harry and Eva (nee Towers). Unfortunately, his father Harry was killed in a saw mill accident a few months before he was born. And Eva and her son (my dad) moved back to Wisconsin with her mother. Eva died a short while later, said to be of a broken heart. And when he was of age, the Towers family sent my dad to Chicago where he earned his degree in engineering.

While still a young man, he joined the army and was in the Spanish-American war that centered around the island of Cuba.

A short while after that he came to northern Minnesota where engineers were needed in the thriving forest industry that was busily cutting, hauling and milling giant first-growth trees on land that had never previously been logged. From there, he became the city engineer in Bemidji where he built roads, bridges, and buildings that still exist today. That’s also where he met my mother who was working as a seamstress at that time.

Cashing in on his military experience, he became a major in the National Guard and when the U.S. entered World War I he was commissioned a lieutenant in the regular army and was assigned to a supply depot in Charlotte, North Carolina. After that war ended he became the city engineer in Charlotte.

Apparently life for the family there had moved up to first class accommodations. My sisters recalled him dressing in linen suits and driving a large Packard—the luxury car of choice at that time–and living directly across the park from the Duke mansion. But, as it turned out, all was not good, though that’s another story to be picked up later in our exploratory tale of life in a small Minnesota village.

The biggest problem I had in Osage was getting books to read. There was no library. There was a Carnagie-endowed library in Park Rapids, but I had no way of getting there. Also, I wouldn’t have felt comfortable in their library simply because I didn’t live in that town and therefore presumed their library was for them only, and not for me.

My brother bought me a book once, Captains Courageous, by Rudyard Kipling. Eleanor also used to buy some of the classics for me, Tolstoy and some of the English authors like Thomas Hardy. Books were rather cheap at that time, so when I would get some money I would buy them through the mail.

One time, for some reason unknown to me, someone gave my mother a set of law books. I read every line in them. They were summaries of thousands of legal cases which included a discussion of the facts presented in each case and the rulings issued by the judge. I found them not only logical, but truly fascinating.

In my room upstairs in my mother’s new house, I had a closet on one side of the room where I kept all of my books and magazines. In the closet on the other side of my room I kept my clothes. In front of a double window I had a rather large, rectangular table which I used as a desk. Behind it was a double bed and next to that a dresser.

At night, I would set at the desk and write short stories in long hand. These gems I would send off to the Saturday Evening Post or Colliers. Sure enough in a couple of weeks I would get a printed rejection notice back in the mail. It never occurred to me at that age, that no one at either magazine would bother to read an unsolicited hand-written submission from a kid.

I should have realized early on that I didn’t really have a flare for words. The first word I ever said was when my grandfather held me up in his living room in front of a mounted deer head with a massive rack of antlers. “What is that, Tommy?” he asked. “Cow,” I confidently replied.

In the first house where we lived on our own next to the store, I was still only in the first or second grade of school. When it came time to go to bed, my mother would send me upstairs to my room with a lighted kerosene lamp in one hand and a glass of water in the other. One slip on the wooden stairs and the kerosene lamp would have become a Molotov cocktail. (In years later, I would never have been able to place that amount of trust in a kid whose hands were barely large enough to reach around the base of a lamp where it thinned into a handhold.)

There was no heat in the room, but it was located directly over the wood stove in the living room on the first floor. Fortunately there was a grate in the floor so some heat could come through. Unfortunately, my mother could look up at the grate and be able to see whether I had blown out the kerosene lamp or was sneaking in some reading time. Always in the winter time, the glass of water on the night table would be frozen solid in the morning. In my flannel PJs and flannel sheets and wool blankets I was warm enough until I stepped onto the bare linoleum in the morning.

You’ve no doubt heard all the stories about the underprivileged kids who had to go to the old two-room schools. Let me tell you something about them that you’ve probably never realized. It’s true, the subject matter was limited: Reading, writing and arithmetic, and a smattering of history. But, the strong points were that you had four years, not just one, to assimilate everything they taught. For example in the first grade you not only were given first-grader material, but you also listened to the same teacher explaining the courses to the second, third and fourth graders. And when you were in the upper grades you again heard a review of all the material from the lower grades you’d already finished so if you missed anything the first time around, you had three more years to get it straight. By the time I reached the fourth grade, I could have written everything on the blackboard that the teacher was about to write.

It was only after I moved into the ‘big room’ that my new teacher noticed my handicap. I didn’t know what she was going to write on the blackboard so I leaned way out of my seat to be close enough to read what was written.

Once every several months, a traveling optometrist came through Osage. He had a small trailer with eye charts on one end and a box with hundreds of prescription lenses on the other. He would hold a different lens up to your one open eye and ask you to read the chart that he had just turned over on the far wall so that you weren’t able to memorize it. Believe me, every kid tried to memorize it because no one wanted to wear glasses. Mine were oval with steel frames and very strong prescriptions. This I regarded as a real tragedy because I had my heart set on being a fighter pilot in the newly organized Army Air Corps that was just being developed.

Plan B, as it happened, was where I eventually ended up in my Army career: Infantry.

I guess you could be practically blind and still be inducted into the infantry. I remember after basic training in WWII we were given a two-week course in jungle training. One of the tactics was to have the squad lay down covering fire on a pillbox while one member of the squad crept up close enough to the pillbox to throw a live grenade in through the aperture just as the squad lifted fire. However, as I was raising up to toss the grenade one member of the squad began peppering the pillbox with rifle fire. I could hear the bullets zinging around my head like angry bees. Fortunately, the lieutenant was able to run up and stop him from firing before he hit me. The next day he was reassigned, hopefully to some branch that didn’t carry lethal weapons.

By the way, the jungle training was unnecessary. As I was in Fort Ord, California, learning how with a full field pack, rifle, and ammunition to climb down the side of a ship on a rope ladder into a landing craft. Before I could embark for the Pacific, my orders were changed from the Pacific to Europe. I can only presume that the decision had been made at that time to drop the two atomic bombs on Japan obviating the necessity for a troop invasion there. (By the way, the trick for climbing down a rope net off a ship onto a landing craft is to only hold on to the vertical not the horizontal ropes. The reason is that there will most likely be someone above you also coming down and he is very likely to step on your hands with size 13 combat boots.)

The rope ladder was the simplest of the invasion techniques a soldier had to learn. One that was a little more tricky was swimming the length of a football field underwater without coming up to breath. The reason preventing you from surfacing was because they had purposefully spilled and ignited gasoline to make the exercise more realistic. I think they termed it, as I recall, how to evacuate a bombed ship. It made me happy I was in the infantry on terra firma rather than in the navy.

One of my saddest performances as a kid had to do with dentists. I often suffered toothaches. Mainly because my diet of choice was candy, ice cream and soda pop, as soft drinks were called then. And also because I rarely, if ever, brushed my teeth. The stopgap remedy for a toothache was to stuff the cavity with cloves. This usually relieved the pain enough or, perhaps distracted you from the pain since they had a most unpleasant taste, so that you could sleep at night.

The next day was the real problem for me.

My poor sister, Eleanor, was usually the one designated to accompany me to the dentist. Her usual plan was to bribe me with a chocolate milk shake after the dental ordeal. That was enough to get me into the dentist’s office which was in an apartment on the second floor of one of the Main Street buildings in Park Rapids. Everything would go okay until I saw him coming toward me with what was to me a gigantic pair of pliers. With that I was out the door.